Irving Penn (1917-2009), recognized as one of the masters of photography of the twentieth century, is widely admired for his iconic images of high fashion and for the remarkable portraits of the artists, writers, and celebrities who defined the cultural landscapes of his time.

Drawing inspiration from Resonance, an exhibition organized by the Pinault Collection in 2014 at the Palazzo Grassi in Venice, the exhibition Untroubled seeks first and foremost to pay tribute to the photographer’s unique legacy.

At the heart of the resonance throughout Penn’s prolific body of work is the lasting influence of the core photographic principles he studiously developed early on. The serene consistency of his image production is deeply indebted to his scrupulous efforts, through the years, to abide by the technical and artistic commands he devised for himself. This self-imposed discipline result in a nearly flawless production.

Penn’s principles remain to this day as relevant as ever, so much so that they are still regarded as empirical truths in spite of the socio-economical, philosophic and aesthetic upheavals of a world that is constantly reinventing itself.

Exhibiting the work of Irving Penn to mark the opening of a new center for contemporary image production is a mission statement, one that embraces the history of photography and the work of the late masters while looking to the future. Penn’s work is a monument of epic artistic resilience, a major reference for contemporary photography and an endless source of inspiration for generations to come.

All the photographs that appear in this exhibition are drawn from the Pinault Collection. Although in date they span more than four decades, they are presented not as a retrospective but are loosely arranged by subject.

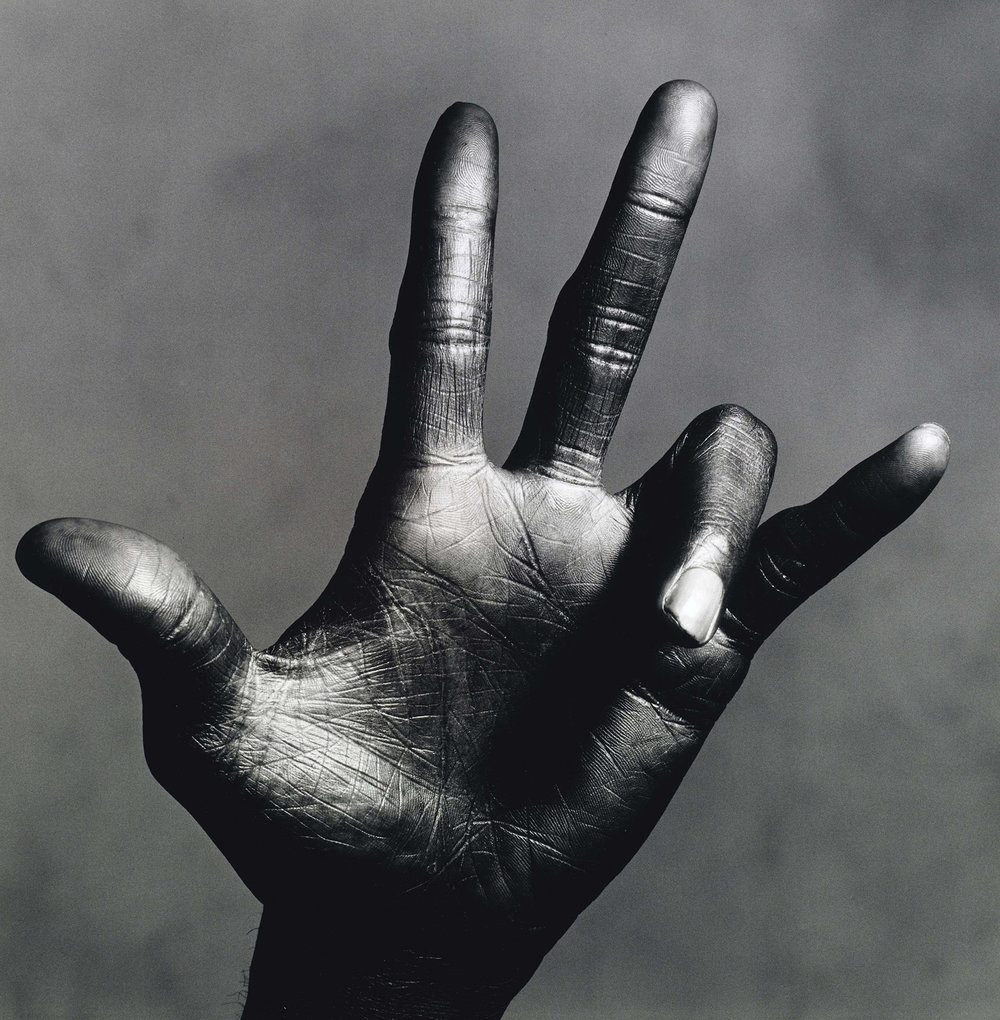

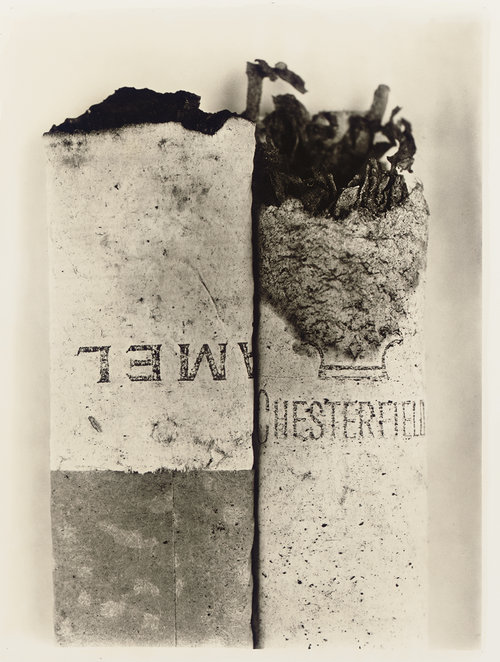

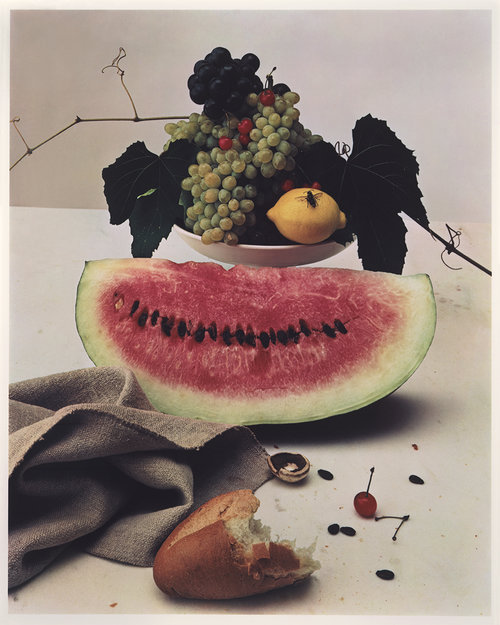

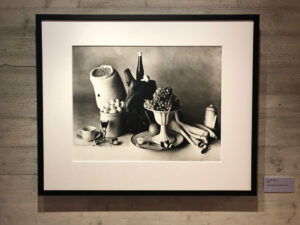

Penn was first and foremost a studio photographer. His photographs, with their simple backdrops of paper, canvas, or bare wall, establish a spatial container at once formal and insular. Whether haute couture, still life, ethnography, or memento mori, the image is decontextualized, intense and demanding of attention.

Penn’s subjects appear at first glance to be quite disparate – celebrities, skulls, cigarette butts. But removed from their natural environment and with an unflinching focus on their materiality, they achieve a democratic leveling that is the signature of Penn’s style. Each subject is equal under his gaze, a quiet yet insistent intruder into the neutral space of the studio.

Trained as a painter, with photography as a side interest, Penn went on to study commercial art and was eventually hired in 1943 as assistant to Alexander Liberman, art director of Vogue in New York, who will become a life-long mentor and friend. That same year he began working for the magazine as a staff photographer and soon established himself as the most innovative professional in the field.

Penn’s commercial success did not inhibit but rather fueled his personal artistic experimentation. In 1949-50 he embarked on a series of nudes that were remarkable for their abstraction. Unlike his work for the magazine, where the printing was in the hands of technicians and the images were made for wide distribution, in these photographs Penn had total control over every aspect of the printing. This first experience of close involvement with the print led him to investigate other processes in the 1960s, among them platinum-palladium printing. Practiced early in the twentieth century, the platinum process created an image that is virtually unlimited in its range of tonal variation. The various aesthetic possibilities of the platinum printing process also inspired Penn to revisit earlier work, printing in platinum and palladium photographs that he had originally printed in universally used gelatin silver. Indeed, the constant reworking of image would provide the fundamental structure of Penn’s creative approach.

The exhibition thus presents the photographs not in a linear, chronological sequence but arranged in a manner that brings out their subliminal affinities. Commercial projects cohabit with ethnographic studies, discarded refuse with sophisticated models, cultural celebrities with animal skulls.

As Penn remarked, “It is all one thing”.